Water Well Drilling in Texas: Geology, Regulations, and Key Resources

Texas offers diverse groundwater conditions and a complex regulatory framework that water well professionals must navigate. This article provides a detailed overview of Texas’s geological aquifer systems, outlines the permitting and licensing requirements for drilling water wells, identifies the major agencies involved in groundwater regulation, and highlights essential forms, databases, and practices (like utility clearance) relevant to drilling in the state. It is written for researchers and industry professionals seeking technical insight into water well drilling in Texas.

Texas Aquifers and Geological Conditions

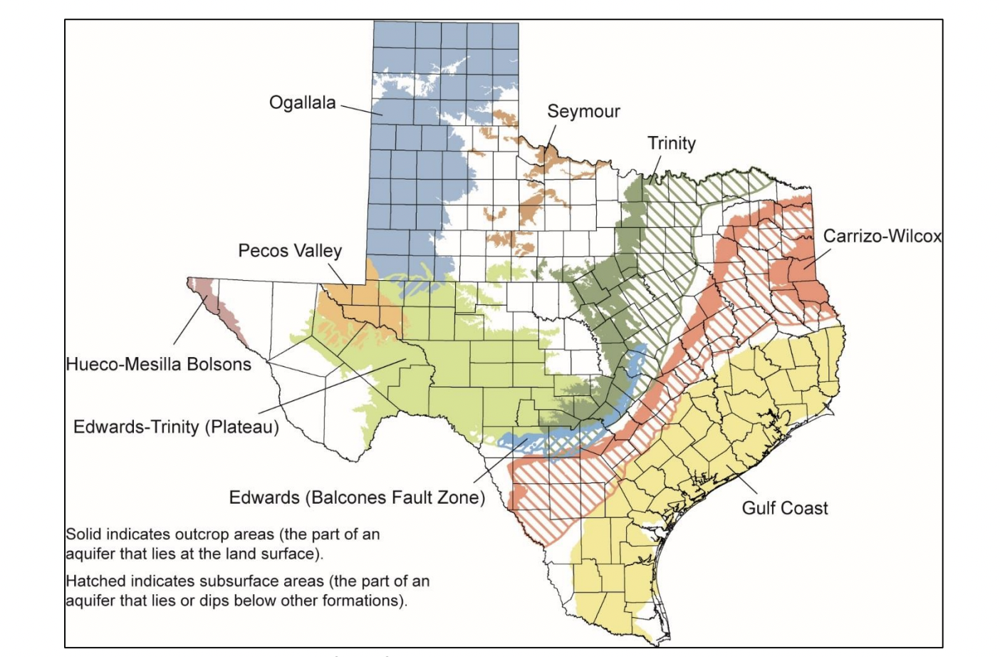

Ogallala Aquifer (High Plains): The Ogallala underlies the Texas Panhandle and South Plains and is the primary source of irrigation water for that region. It consists of unconsolidated sands and gravels with relatively high permeability. Wells are typically a few hundred feet deep and can yield large volumes; in parts of the High Plains, irrigation wells historically produce hundreds of gallons per minute (commonly 200–800+ GPM)'. In some counties, Ogallala wells have yielded up to ~1,000 GPM under favorable conditions'. However, the saturated thickness of the Ogallala is declining in many areas due to extensive pumping, and recharge is limited (only on the order of half an inch per year in the High Plains)'. This aquifer’s water is generally fresh and used heavily for agriculture and municipal supply.

Edwards Aquifer (Balcones Fault Zone): The Edwards BFZ Aquifer is a famous karst limestone aquifer in Central Texas, spanning areas around San Antonio and Austin. It is characterized by cavernous, fractured limestone with exceptionally high permeability and spring discharge (e.g. Comal Springs, Barton Springs). Edwards wells are typically a few hundred feet deep (often in the 300–800 ft range) and are known for extremely high yields – often several hundred to over a thousand gallons per minute in productive zones. In fact, average well yields in the Edwards Aquifer are **orders of magnitude** higher than those of the neighboring Trinity Aquifer in the Hill Country'. (One study noted Edwards wells had about 250 times the yield of Hill Country Trinity wells on average'.) The Edwards is highly responsive to rainfall and recharge; it acts like an “underground lake” in contrast to the Trinity’s slower, more stagnant system''. Water from the Edwards is generally fresh and feeds many springs; the aquifer supports large municipal pumping for San Antonio. Because of its karst nature, it is very susceptible to contamination and is carefully managed.

Trinity Aquifer (Hill Country): The Trinity Aquifer underlies much of the Hill Country and extends northward to the Dallas–Fort Worth area. In the Hill Country, the Trinity is a limestone and sandstone aquifer with relatively low permeability (often described as a fractured-rock “sponge”). Wells in the Trinity typically must be drilled deeper (commonly 300–1,000+ ft to tap the Middle or Lower Trinity units) and often have low yields. In many Hill Country areas, a Trinity well might yield only a few gallons per minute to a few tens of GPM'. (Wells yielding 0.5–5 GPM are not uncommon, though some may reach 50+ GPM in better fractures.) These yields are far lower than those of the Edwards; as noted, on average the Trinity’s well yields can be roughly 1/250th of Edwards wells in adjacent areas'. Water levels in Trinity wells can fluctuate significantly during droughts, and some wells run dry when stressed'. The Trinity’s limited productivity and slow recharge (only an estimated 4–10% of rainfall percolates down to it') make groundwater management challenging in fast-growing Hill Country communities.

Gulf Coast Aquifer (Coastal Plains): The Gulf Coast Aquifer is a major water source for Southeast Texas, including the Houston metropolitan area and Gulf Coast agriculture. It is composed of layered sand, silt, and clay formations (such as the Chicot, Evangeline, and Jasper aquifers, separated by clay confining beds). Well depths in the Gulf Coast aquifer vary from shallow (a few hundred feet near the coast or outcrop) to very deep (wells may exceed 2,000–3,000 ft in downdip areas where fresh water is found)'. This aquifer can provide high yields, especially in thick sand sections; for example, municipal wells around Houston commonly yield on the order of 1,000–1,800 GPM'. The aquifer’s water quality is generally good for the upper portions (fresh water typically occurs to about 3,200 ft deep in the northeast trend)', but salinity increases toward the coast and with depth (leading to brackish water or saltwater intrusion in some areas'). Heavy pumping in the past led to significant land subsidence in parts of the Gulf Coast. Groundwater conservation districts now regulate pumpage around places like Houston/Galveston to mitigate subsidence and saltwater intrusion, and usage has shifted partly to surface water.

Other Aquifer Systems: Texas’s other major aquifers include the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer (stretching across East Texas into South Texas), which is a thick sand aquifer system providing moderate to high yields (often 100–500 GPM for municipal and agricultural wells) and used widely for rural water supply. The Seymour Aquifer (in North Texas) is a shallow alluvial aquifer with variable yields, and the Pecos Valley Aquifer (West Texas) and Hueco-Mesilla Bolsons (Far West Texas) serve as important sources in their regions. The Edwards-Trinity (Plateau) Aquifer of West-Central Texas underlies the Edwards Plateau and can have locally productive wells (it is the continuation of Edwards and Trinity units in a different setting). In some west Texas counties (e.g. Pecos County), wells completed in the Edwards-Trinity or associated limestones can be very high yielding – average well yields of 400 up to 3,000 GPM have been noted in certain areas with favorable conditions'. Overall, the productivity of a well in Texas depends heavily on the aquifer tapped: large irrigation or public supply wells in prolific aquifers (Edwards, Ogallala, Gulf Coast) may yield hundreds to thousands of GPM, whereas wells in tight rock aquifers (Trinity, minor aquifers) might only yield a few GPM.

Permitting Requirements for Water Well Construction

Texas groundwater law is unique in that it historically follows the “rule of capture,” meaning landowners can pump groundwater from beneath their land with few state restrictions. However, modern regulations at the local level have introduced permitting requirements in many areas. There is no single statewide permit for drilling a water well, but local Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs) play a key role in permitting. If a well will be drilled within a GCD’s jurisdiction and is not exempt by law, the well owner must obtain a permit from that GCD before drilling''. GCD permits typically specify the allowable use (e.g. irrigation, municipal, domestic) and may set limits on pumping volumes or rates.

Exempt Wells: Many GCDs exempt certain small-capacity wells from permit requirements. Under Texas Water Code §36.117, domestic and livestock wells on small properties are statutorily exempt if they meet specific criteria. In general, a water well used solely for domestic use or for livestock/poultry on a tract of land larger than 10 acres is exempt from permitting provided it is drilled, equipped, or completed so that it cannot produce more than 25,000 gallons per day (about 17.3 GPM) Areas with No GCD: Not all parts of Texas are covered by a groundwater district. In areas with no GCD, landowners do not need a local permit to drill a water well, but they still must adhere to state regulations (and should still use a licensed driller). In such “rule of capture” areas, a landowner can drill and pump groundwater essentially freely (for beneficial use) – but note that if a new GCD is created or an existing one annexes the area in the future, that well would then become subject to the district’s rules. It’s advisable to check with the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (TDLR) or Texas Water Development Board for any regional or county-specific requirements in areas lacking a GCD. Additionally, some counties or municipalities have ordinances (for example, setback requirements for wells near septic systems, or plugging of abandoned wells), but primary oversight is through the state and GCDs. State Notification: Texas does not require obtaining a state-level drilling permit for a water well, but drillers are obliged to submit well reports to the state (discussed later) and must follow construction standards set by state rules. If the well will serve a public water system, coordination with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) is required for sanitary control easements and approval of well siting and construction standards (public water supply wells in Texas have to meet TCEQ’s rules for casing, grouting, separation from contamination sources, etc., typically under 30 TAC Chapter 290). In summary, before drilling any water well in Texas, the driller or well owner should: Water well drillers in Texas must work within a regulatory framework that involves several state and local agencies. The major entities include: Proper documentation and data access are critical aspects of water well drilling in Texas. The state has official forms that must be used for reporting well completions, and it provides public databases where these records can be accessed. Key resources include: Well Completion Reports (Driller’s Logs): Every licensed driller is required to submit a well report for each new well drilled, typically within 60 days of completing the well. This report documents the well’s location, depth, construction details, geology encountered, and completion information. The official form is the State of Texas Well Report (TDLR Form #WWD-001)Well Report Submission Form (Form #WWD-002) for use if mailing in reports'. Many drillers now submit well reports electronically via the online system, but whether submitted online or by paper, the same information is required. These well reports become part of the public record. The driller must also provide a copy of the report to the well owner and, if within a GCD, often to the local district as well. (Under Texas law, well reports can be made confidential at the owner’s request, but generally they are public unless an owner has sought confidentiality)'. Online Well Report Databases: Modern well reports (generally wells drilled 2003 to present) are entered into the TWDB-TDLR database called the Submitted Drillers Reports (SDR) database'. The TWDB hosts an online search tool and map viewer for these records. Users can go to the TWDB Water Data Interactive Groundwater Viewer to search for well reports by location, well depth, aquifer, driller, etc. :'. This interactive map includes both the SDR database records and older TWDB Groundwater Database (GWDB) records. For wells drilled before the SDR system (pre-2003), the primary source is the TCEQ Water Well Report Viewer mentioned above, which allows one to click on a map and view scanned images of well reports'. The TCEQ viewer is useful for historical research, as it contains many legacy well logs submitted by drillers to the predecessor agencies. Between the TWDB interactive viewer and the TCEQ viewer, drillers can retrieve most well logs in Texas by either geographic search or by a state-issued tracking number. The TWDB also offers bulk downloads – for instance, the entire well report database and GIS shapefiles of well locations can be downloaded for analysis''. Groundwater Data and Publications: In addition to well logs, Texas provides a wealth of groundwater data useful to drillers. The TWDB’s Groundwater Data section includes water level measurements, pumping data, aquifer properties, and water quality data from thousands of monitoring wells statewide. The agency publishes reports on each aquifer (e.g., Aquifers of Texas, Report 380) and Groundwater Availability Models (GAMs) which predict aquifer behavior. Drillers might also use the Texas Water Development Board’s “Brackish Aquifer” datasets if dealing with brackish water. Another useful resource is the Texas Groundwater Protection Committee FAQs, which list state and federal groundwater databases and tools''. For example, the TGPC points to the USGS National Water Information System for additional well records and the Texas Alliance of Groundwater Districts database for district-specific well information''. Lastly, the Texas Well Owner Network (AgriLife Extension) and various regional water planning groups provide public information on local groundwater conditions that can be useful when planning a new well. Before any drilling begins, it is essential to ensure there are no conflicts with existing underground utilities at the site. Texas law **requires** anyone who excavates or drills in the ground to notify utility operators in advance. The statewide one-call notification system is accessed by dialing 811 (Texas811). By law, an 811 notification must be made at least two business days (excluding weekends and holidays) before digging'. This requirement applies even on private property – for instance, a rancher drilling a well on his own land is still obligated to call 811 beforehand. When you call Texas811, utility companies (water, gas, electric, telecommunications, pipelines) will be notified to come mark the location of any buried lines or cables at the drilling site. Failing to call 811 can lead to dangerous accidents (hitting a gas line or electrical line) and legal liability. In practice, drillers should incorporate the 811 call into their pre-drilling checklist. The call and marking service are free. After the request, wait for all utilities to respond and mark their facilities (typically within 48 hours). Only then should drilling commence, proceeding with caution around any marked areas. By following the “Call Before You Dig” procedure, drillers can prevent utility damage and ensure a safe drilling operation'. Driller Licensing and Qualifications: As noted, Texas requires well drillers to be licensed professionals. To obtain a license, an individual must meet experience requirements (at least two years of relevant experience, or completion of a defined number of wells under supervision) and pass a comprehensive exam on drilling techniques and state rules''. There is no formal degree requirement, but knowledge of geology and hydrology is beneficial'. Once licensed, drillers must renew their license periodically and complete continuing education courses to stay up to date on regulations and best practices. Working as an unlicensed driller is illegal and can result in significant penalties. The license requirement helps ensure that wells are constructed properly to protect groundwater resources from contamination'. Drilling firms often employ multiple licensed drillers and crews, as well as apprentices registered with TDLR. If you are hiring a driller, you can verify their license on the TDLR website. Pump installers must also be licensed by TDLR, as they often complete the well by installing pumping equipment and must ensure the wellhead is finished out correctly. Well Construction Standards: Texas has detailed well construction and plugging specifications codified in the Texas Administrative Code, Title 16, Chapter 76 (the Water Well Drillers and Pump Installers rules). These statewide standards cover requirements such as: minimum casing thickness, when and how to install surface casing, annular space sealing (e.g. requiring cement or bentonite grout from ground surface to a certain depth to prevent contamination migration), screening and sand pack, and proper sealing of well caps. They also define the required setbacks (for example, a water well must be a set distance from septic systems, feedlots, or potential pollution sources). Drillers must construct wells in compliance with these rules. Local GCDs might have additional construction standards or references to these rules in their bylaws. The driller’s well report includes a section where they certify the well was completed in accordance with the law and that any encountered bad water or injurious constituents were handled properly'. Notably, if a driller penetrates a zone of poor-quality water (saline or polluted water), they are legally obligated to inform the landowner and ensure that zone is isolated (either by casing and cement or by plugging), to avoid contamination of fresh water aquifers''. Abandoned wells must be plugged according to state guidelines (typically by filling with cement or bentonite to seal the entire borehole) – the TDLR provides a well plugging report form (WWD-004) and the TCEQ publishes a manual for landowners on how to plug wells properly. Reporting and Recordkeeping Obligations: After completing a well, in addition to the state well report, drillers may have to file other reports. If the well encountered undesirable water (as mentioned above), a specific “Report of Injurious Water or Constituents” (Form WWD-003) should be filed'. Many GCDs require a copy of the state well log and sometimes a registration form to be submitted to the district. Some districts also ask for pump test data if available. Drillers should maintain their own logs and copies of reports for their records and for the well owner. Texas water well reports are public records, and in fact the TWDB encourages drillers and owners to use its databases to research nearby wells (for instance, to gauge what aquifer and depth might yield the best water). Well owners are also advised to keep the driller’s report permanently, as it contains valuable information about the construction and local geology that may be needed for future maintenance or if the well is reworked. Groundwater Management Rules (GCD Enforcement): Groundwater Conservation Districts enforce rules that can affect day-to-day operations of wells. For example, a GCD may have spacing rules – e.g., a new high-capacity well might need to be at least X feet from the nearest existing well or property line per the district’s spacing matrix (often based on pump size or acreage). They may also enforce production limits, such as allocating a certain amount of pumping per acre of land or capping the total volume per year. During drought conditions, many GCDs invoke drought contingency rules that require mandatory pumping cutbacks or watering restrictions for certain permit holders. It’s important for drillers to inform clients that having a GCD permit doesn’t guarantee unlimited water – the permit will be subject to the district’s rules and any future changes (like new conservation rules or alterations in Desired Future Conditions). Some GCDs (especially in critical areas like the Edwards Aquifer Authority) have metering requirements, so large wells must have flow meters installed and readings reported regularly. Drillers involved in those projects may be responsible for installing approved meters and informing owners of reporting duties. In sum, drillers need to be aware of the local GCD’s rules not just for the drilling phase but for how the well will be operated, to ensure the well is compliant (for instance, constructing the well to a diameter that matches the permitted pump size, etc.). The Texas Alliance of Groundwater Districts maintains a GCD Index and map that drillers can consult to find the relevant district and its rules for any given area''. By understanding the geological context of the drilling site, securing the proper permits, and adhering to state and local regulations, water well drillers in Texas can successfully develop groundwater resources while protecting the environment. Always leverage the available resources – from aquifer maps and well databases to agency guidance documents – to plan and execute drilling projects effectively. Texas’s combination of abundant aquifers and robust regulatory oversight means that informed, compliant drilling practices are not just recommended but required for long-term sustainable groundwater development. Sources: Key information for this article was drawn from the Texas Water Development Board (aquifer descriptions and maps)'', Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (well driller rules and forms)'', Texas Groundwater Protection Committee and TCEQ resources (groundwater data and well viewer)'', and various groundwater district publications.

Key Agencies Involved in Groundwater and Well Regulation

Well Logs, Forms, and Groundwater Data Resources

Utility Clearance Before Drilling (Texas811)

Other Important Considerations for Drillers in Texas